Terry Pratchett

2000

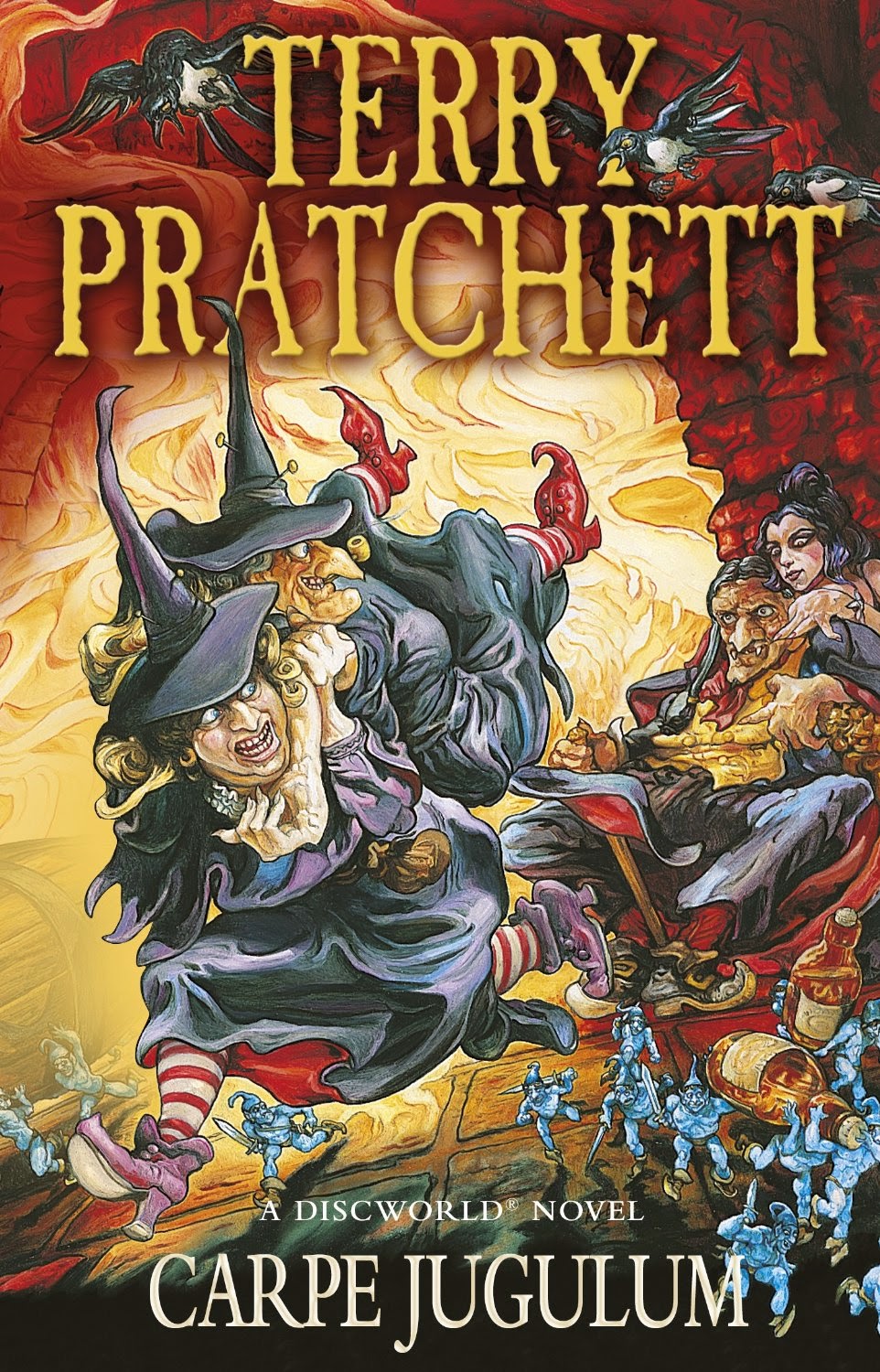

Other Terry Pratchett Reviews- Colour of Magic - Light Fantastic - Equal Rites - Mort - Sourcery - Wyrd Sisters - Pyramids - Guards! Guards! - Eric - Moving Pictures - Reaper Man - Witches Abroad - Small Gods - Lords & Ladies - Men At Arms - Soul Music - Interesting Times - Maskerade - Feet of Clay - Hogfather - Jingo - Last Continent - Carpe Jugulum - Fifth Elephant - Truth - Raising Steam - Blink of the Screen - Sky Adaptations - Video Game 1 - Pratchett Portfolio - Dodger - Long Earth

After the personal disappointment of The Fifth Elephant, where the sinister political machinations of the dwarves conspired only to put me to sleep, we move on to the twenty-fifth book in the series and a novel which more successfully promotes a different type of world-building. Although I seem to be saying this with each review for various reasons, this is another personal landmark in my own journey through the Discworld series; marking the very first time I purchased one as a newly-released hardback- using my own hard-earned (well, sort of) cash from my first ever real job. I remember the pride and joy I felt as I added the luxurious, beautifully-covered tome to my collection (otherwise comprised of well-worn paperbacks), with the hope of many more to come. Now I look at the ridiculously over-sized damned things and think about somehow trading them in for paperback versions, lest my bookshelf collapse. The folly of youth, etc.

So then, as I was saying, The Truth is one of the most direct examples of Pratchett performing an important new piece of world building; creating his own version of an ubiquitous human standard to not only directly add a new feature to the daily lives of Ankh-Morpork's fair citizens but also to signify a permanent shift in his future portrayals of the Disc's chief city. Through the events of this novel and many more to follow, the city moves forward from its origins as a kind of mishmash of medieval-to-seventeenth century England, and hurtles towards a more progressive mish-mash of eighteenth century and Victorian England. This time out a young man named William de Worde takes the city by storm by unwittingly inventing the newspaper industry.

.jpg) As has been mentioned before here, the key essence to the transformation

is Pratchett's determination to add further order and stability to a

previously chaotic environment, something he started doing as far back

as Guards! Guards! with the rebirth of the city watch. The concept of a daily newspaper is an obvious one in hindsight, and offers Pratchett a number of ways to incorporate his typical satire and parody, the former emanating from his own experiences as a journalist. Pratchett comes up with an original core cast of characters (with supporting aid from some of the usual suspects, of course including Sam Vimes), led by de Worde, himself the bored and ingenious son of a nobleman looking to shake things up for himself.

As has been mentioned before here, the key essence to the transformation

is Pratchett's determination to add further order and stability to a

previously chaotic environment, something he started doing as far back

as Guards! Guards! with the rebirth of the city watch. The concept of a daily newspaper is an obvious one in hindsight, and offers Pratchett a number of ways to incorporate his typical satire and parody, the former emanating from his own experiences as a journalist. Pratchett comes up with an original core cast of characters (with supporting aid from some of the usual suspects, of course including Sam Vimes), led by de Worde, himself the bored and ingenious son of a nobleman looking to shake things up for himself.

de Worde seems most likely a prototype character for the more successful later creation of Moist von Lipvig (of Going Postal, Making Money and Raising Steam fame), but one who unfortunately lacks the interesting backstory and lovable roguishness of Moist, and therefore the overall charisma to go with it. His inevitable love-interest comes in the form of investigative reporter Sacharissa Crisplock, while the comic relief is supplied by vampire photographer Otto von Chieck, who has the unfortunate habit of disintegrating into dust every time he uses the flash function. Together they create The Ankh-Morpork Times, and a selection of new enemies to go with it.

Though the characters seemingly didn't have enough interest in them to justify a reoccurring position in the Discworld series as Moist later did, they fit the story of this book well enough, as somewhat hapless idealists who stumble into more trouble than they'd anticipated when they discover a plot to frame the Patrician for murder. Switching back and forth neatly between the corrupt wealthy gentry of the city and their vicious musclemen on the street helps put the city in a nice new perspective, and lets Pratchett have a ton of fun with the gangsters and hoodlums motif, notable parodying Pulp Fiction on numerous occasions amongst other things. Against all odds William and co. manage to delve to the truth of the matter, uncover the sinister plot, then ride off into the background of the city, rarely to be mentioned again.

Perhaps The Truth looks that much better to me in direct comparison to The Fifth Elephant, where the condensed scale of the events and unassuming, sometimes idiotic characters were a pleasant relief. Pratchett's increasing tendency to make far too many of his characters incessantly wise can sometimes go too far in hurting his books, and so I'm always more of a fan of his dumber characters (after all, the success of the Discworld series was based on the general idiocy of its most popular character in Rincewind). The fairly simple nature of the plot doesn't hurt it at all, since Pratchett's witty and evocative depictions of Ankh-Morpork from the viewpoint of a reporter make up for that.

Overall then, a funny, compelling page-turner with fresh characters that doesn't do anything ground-breaking by itself but does represent a further shift in scenery. It also sits nicely as a refreshing breather for Discworld fans, sat in-between the annoyingly concrete political shifting of Fifth Elephant and upcoming apocalyptic high-fantasy of The Thief of Time- of course the subject of our next Discworld review, and Death's final leading role.

"WHO KNOWS WHAT EVIL LURKS IN THE HEART OF MEN? The Death of Rats looked up from the feast of potato. SQUEAK, he said. Death waved a hand dismissively. WELL, YES, OBVIOUSLY ME, he said. I JUST WONDERED IF THERE WAS ANYONE ELSE."

After the personal disappointment of The Fifth Elephant, where the sinister political machinations of the dwarves conspired only to put me to sleep, we move on to the twenty-fifth book in the series and a novel which more successfully promotes a different type of world-building. Although I seem to be saying this with each review for various reasons, this is another personal landmark in my own journey through the Discworld series; marking the very first time I purchased one as a newly-released hardback- using my own hard-earned (well, sort of) cash from my first ever real job. I remember the pride and joy I felt as I added the luxurious, beautifully-covered tome to my collection (otherwise comprised of well-worn paperbacks), with the hope of many more to come. Now I look at the ridiculously over-sized damned things and think about somehow trading them in for paperback versions, lest my bookshelf collapse. The folly of youth, etc.

.jpg) As has been mentioned before here, the key essence to the transformation

is Pratchett's determination to add further order and stability to a

previously chaotic environment, something he started doing as far back

as Guards! Guards! with the rebirth of the city watch. The concept of a daily newspaper is an obvious one in hindsight, and offers Pratchett a number of ways to incorporate his typical satire and parody, the former emanating from his own experiences as a journalist. Pratchett comes up with an original core cast of characters (with supporting aid from some of the usual suspects, of course including Sam Vimes), led by de Worde, himself the bored and ingenious son of a nobleman looking to shake things up for himself.

As has been mentioned before here, the key essence to the transformation

is Pratchett's determination to add further order and stability to a

previously chaotic environment, something he started doing as far back

as Guards! Guards! with the rebirth of the city watch. The concept of a daily newspaper is an obvious one in hindsight, and offers Pratchett a number of ways to incorporate his typical satire and parody, the former emanating from his own experiences as a journalist. Pratchett comes up with an original core cast of characters (with supporting aid from some of the usual suspects, of course including Sam Vimes), led by de Worde, himself the bored and ingenious son of a nobleman looking to shake things up for himself.de Worde seems most likely a prototype character for the more successful later creation of Moist von Lipvig (of Going Postal, Making Money and Raising Steam fame), but one who unfortunately lacks the interesting backstory and lovable roguishness of Moist, and therefore the overall charisma to go with it. His inevitable love-interest comes in the form of investigative reporter Sacharissa Crisplock, while the comic relief is supplied by vampire photographer Otto von Chieck, who has the unfortunate habit of disintegrating into dust every time he uses the flash function. Together they create The Ankh-Morpork Times, and a selection of new enemies to go with it.

Though the characters seemingly didn't have enough interest in them to justify a reoccurring position in the Discworld series as Moist later did, they fit the story of this book well enough, as somewhat hapless idealists who stumble into more trouble than they'd anticipated when they discover a plot to frame the Patrician for murder. Switching back and forth neatly between the corrupt wealthy gentry of the city and their vicious musclemen on the street helps put the city in a nice new perspective, and lets Pratchett have a ton of fun with the gangsters and hoodlums motif, notable parodying Pulp Fiction on numerous occasions amongst other things. Against all odds William and co. manage to delve to the truth of the matter, uncover the sinister plot, then ride off into the background of the city, rarely to be mentioned again.

Perhaps The Truth looks that much better to me in direct comparison to The Fifth Elephant, where the condensed scale of the events and unassuming, sometimes idiotic characters were a pleasant relief. Pratchett's increasing tendency to make far too many of his characters incessantly wise can sometimes go too far in hurting his books, and so I'm always more of a fan of his dumber characters (after all, the success of the Discworld series was based on the general idiocy of its most popular character in Rincewind). The fairly simple nature of the plot doesn't hurt it at all, since Pratchett's witty and evocative depictions of Ankh-Morpork from the viewpoint of a reporter make up for that.

Overall then, a funny, compelling page-turner with fresh characters that doesn't do anything ground-breaking by itself but does represent a further shift in scenery. It also sits nicely as a refreshing breather for Discworld fans, sat in-between the annoyingly concrete political shifting of Fifth Elephant and upcoming apocalyptic high-fantasy of The Thief of Time- of course the subject of our next Discworld review, and Death's final leading role.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)