The Wooden-Shelf Thing

I've been putting this off for too long; another look at what's on my ominous to-read shelf. I previously did this with The Glass Cabinet and The Darkened Wardrobe (I have to have stupid names for these things for some reason). A couple of these books have been on there for a long while now...

Bukowski, Charles- Hot Water Music & The Pleasures of the Damned- Poems, 1951-1993

Though I've finished all of Charles Bukowski's novels, there are still a few other volumes of short stories and magazine articles to read, including the story collection Hot Water Music, which I have in a neat minimal paperback from Ecco Press. There's also the matter of Bukowski's poetry. I'm not normally one for poetry, but it would be a crime to read through the author's bibliography without it, and the large collection I have seems a good introduction to it.

Burgess, Anthony- A Clockwork Orange

An unknown number of years before I began this blog, I read an Anthony Burgess novel named 1985, but it just didn't click with me. As a result I think it put a subconcious block in my head against Burgess, so I've voided him ever since- but I still really wanted to get around to reading A Clockwork Orange someday, and now I've finally got him.

Maugham, W. Somerset- The Explorer, The Narrow Corner & Of Human Bondage

Three more entrants from Maugham's extensive bibliography, including his most famous piece. The other two are much smaller, but no less intriguing books in neat little Penguin paperbacks.

Dawkins, Richard- River Out of Eden

Barrow, John D.- The Book of Universes

Pinker, Steven- How the Mind Works

Three books queued up to scratch my occasional popular science itch, recently neglected in favour of a trip through some classsic gothic horror.

Koestler, Arthur- Darkness at Noon

Zamyatin, Yevgeny- The Dragon and Other Stories

Fairly random off the shelf buys, in great little Penguin paperback editions, bought because they just seemed like interesting Eastern European pieces of intellectualism.

MacDonald, John D.- The Deep Blue Goodbye

Thompson, Jim- The Getaway

As I mentioned during my review of Georges Simenon's The Blue Room, I have two other examples from Orion Press' Crime Masterworks series, and these are they. Again, I ignorantly don't really know anything about them, except I'm very excited to read them.

Auster, Paul- The Brooklyn Follies & Winter Journal

My life will never be completed until I've read and reviewed everything by Paul Auster. I read The Brooklyn Follies as a library book a long while ago pre-blog and now need to read my own copy, while Winter Journal is one of two recent pieces of non-fiction from Auster.

Castaneda, Carlos- The Eagle's Gift & A Separate Reality

Peake, Mervyne- Gormenghast

Examples from two cult-classic series that I can't actually read goddamnit because I didn't realise these weren't the first volumes of the series when I bought them. On the back-burner.

Wyndham, John- Stowaway To Mars & The Kraken Wakes

Asimov, Isaac- Foundation, Foundation and Empire & Second Foundation

Roberts, Keith- Pavane

My current slice of to-read sci-fi. I found the Wyndham books randomly second-hand, and having read and enjoyed Day of the Triffids couldn't resist going back to him. As for Asimov, despite him being one of the most famous science fiction writers of all time, I've only read one short story collection from him. The Foundation series was his magnum opus, so if that doesn't click for me then no Asimov novel will. Pavane, meanwhile, is a book included on Orion Press' Sci-Fi Masterworks label.

Amis, Kingley- Lucky Jim

Vidal, Gore- Messiah

Faulkner, William- The Sound and the Fury

Buchan, John- The Thirty-Nine Steps

Four random genre classics I picked up by author reputation and because I'm a literary snob. Faulkner seems the most interesting, though also potentially off-putting if I don't like the ambition style. The Thirty-Nine Steps, meanwhile, I have in an amazing 60's pulp-style paperback that I will continue to love the design of even if I don't like the book. Gore Vidal's book was here the last time I did this, but a little research makes me optimistic.

Capote, Truman- The Complete Stories

Thompson, Hunter S.- The Rum Diary

London, Jack- The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

Three classic US authors whom I've already begun following on this blog and am destined to continue until I inevitably get bored of this thing. I've been meaning to read The Rum Diary for a long time, but never ran across a charity bookshop copy, so had to actually buy one at full price from Amazon. That annoyed me.

Gatiss, Mark- The Vesuvias Club/ The Devil in Amber

This was on the last list I did too, I just can't bring myself to start it. The problem is even though I respect Mark Gattis' TV work in general (well, Sherlock anyway) I'm just severely paranoid that a modern piece of spy fiction genre fiction by a very modern TV comedy/children's sci-fi actor could possibly be any good. I think Douglas Adams warped my standards a long time ago, to be honest. I'll start it soon, but if it doesn't hit quickly it's getting abandoned.

Gide, Andre- The Immoralist

Houellebecq, Michel- Atomised

More (presumably) existential French literature; one a novella from 1902, the other a novel from 1998. Should be interesting, if nothing else.

Steinbeck, John- Of Mice and Men

I haven't read this book for about thirteen years, and it's one of the most important in terms of my own literary development, so I was very happy to find a copy recently.

Rubin, Jay- Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words

This book was on the last list too, but that's just because I've been saving it is the last piece of Murakami-related writing available to me at the moment.

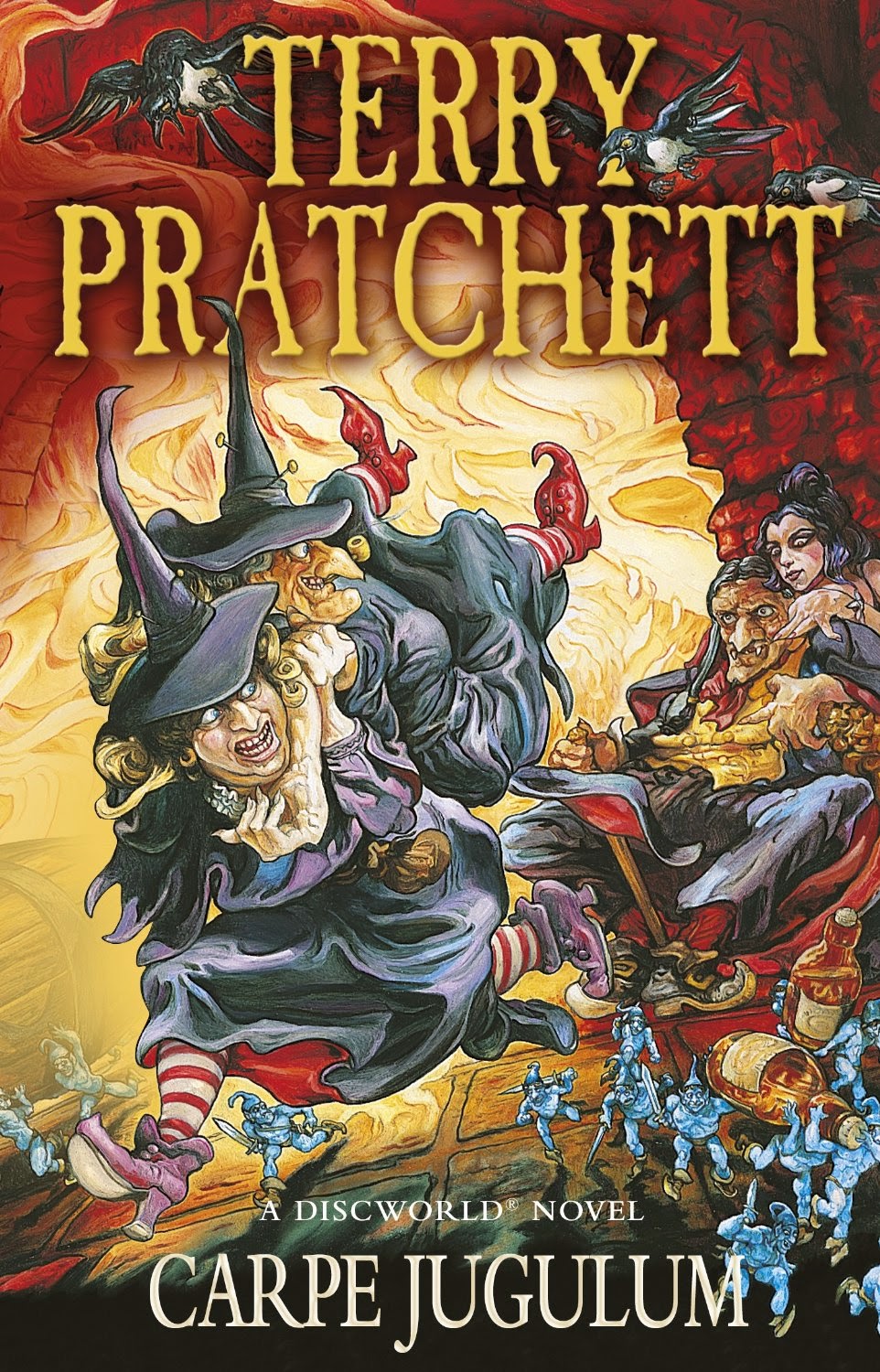

Pratchett, Terry & Kidby, Paul- The Pratchett Portfolio

Pratchett, Terry & Baxter, Stephen- The Long War

Pratchett, Terry, Stewart, Ian & Cohen, Jack- The Science of the Discworld IV- Judgement Day

Because, of course, I can never get enough Terry Pratchett books. The Pratchett Portfolio is a very small volume of art that I'll look at fairly soon. The Long War is the sequel to The Long Earth, which I very much enjoyed and shall likely continue to do so. Science of the Discworld IV is from a spin-off series I've not properly explored, but will have to in order to cover the whole Discworld series eventually (the year 3010, I'm predicting).

And last and probably least...

Martin, George R.R.- A Song of Ice and Fire- A Dance with Dragons 2: After the Feast

The only book to remain on every single one of these lists, meaning it's been waiting on the pile for almost two years. Every day I flirt with giving the entire Song of Ice and Fire series to Oxfam Bookshop, but I never actually get around to it. Still, in all likelihood, I'll probably never read this, the final volume available yet, because George R.R. Martin writes like a severely concussed Tolkien and I'm just not interested in that. The Dan Brown of fantasy, no matter how brilliant the detached TV show genuinely is.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)